NOT ALL TRASH IS CREATED EQUAL

LACMA Exhibit “Kitasono Katue: Surrealist Poet”

Interview with Hollis Goodall, curator, by Aoki Eiko

Editor's note: Kitasono Katue first appeared in the pages of Third Rail in issue no. 7, 1985, brought to my attention by John Solt, who was then literally writing the book on the Japanese dadaist poet and graphic artist. Third Rail was the first to introduce Kitasono's poetry and visual work in the US after he passed away in 1978 (he had been published widely in the West prewar and before he died, as well as in Europe and New Zealand after he passed). Kitasono and the poets of the Vou group were featured in Third Rail two issues later, with Kitasono’s plastic poems and graphics from early issues of Vou magazine, an underground of writers and artists cutting across traditions and disciplines working with avant- garde poetics and aesthetics. Among many compelling aspects of his work, the counter-intuitive juxtapositions of word and image he spliced into the ideational and visual fields of his poems evoked the modern aesthetic of the time of Klee and Kandinksky, but with a zen twist that takes it to a different place. A dissociative linking of unrelated and incongruous objects performs the dadaist act of deflating hierarchies and upending sequences of reason. This man-bites-dog quality in the surprisingly absurdist world of his art and poetry remained an object of fascination since I first pasted his poems and images onto layout boards. A full exhibit devoted to his graphic and photographic work at LACMA was long overdue. Walking slowly through the exhibit was like moving through coexisting levels of visual and linguistic memory. The freshness of Kitasono Katue’s nullification of meaning, even on magazine covers and in other publications and ephemera, opened up unknown possibilities of seeing and knowing. Each concrete poem and graphic image was a prise de conscience calling upon us to short circuit standard tropes of meaning and take measure of reality in terms of the unexpected.

-- Uri Hertz

The exhibit took place on the Felix and Helen Juda galleries of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s “Pavilion for Japanese Art” from August 3-December 1, 2013. Aoki Eiko, a freelance arts-journalist, traveled from Kyoto expressly to see and write about the exhibit, and she was accorded a personal tour and interview by curator Hollis Goodall.

Kitasono Katue (1902-1978) is regarded in Japan as a highly innovative poet, graphic artist and photographer—an avant-garde insurgent—who broke boundaries in all three genres over half a century while simultaneously conducting boundary-crossover works in each of them, all this with a thread of consistency running through it that continues to offer new generations fresh jolts of stimulation. For more about Kitasono at LACMA’s website, including short essays

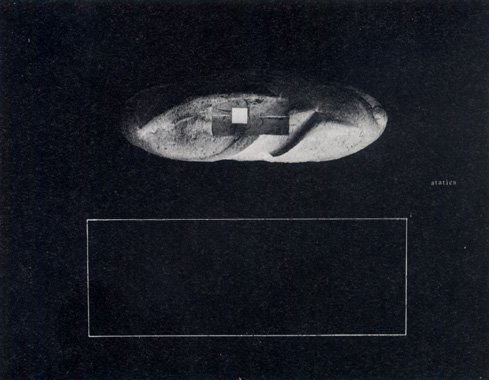

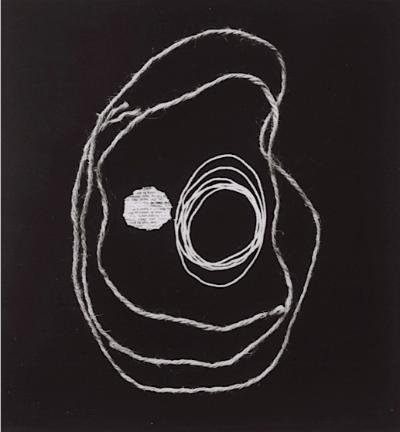

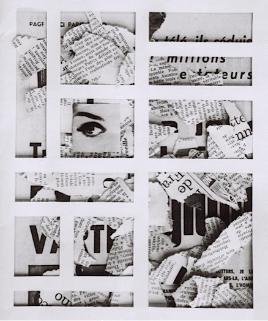

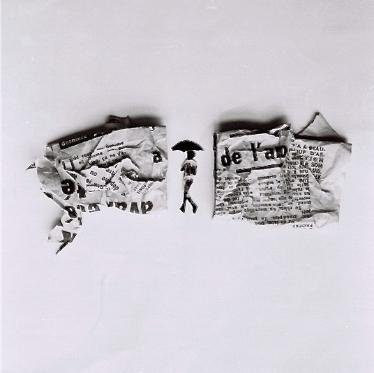

by Aoki Eiko and curator Noda Naotoshi (Setagaya Museum of Art, Tokyo), please see http://lacma.org/art/exhibition/kitasono-katue-surrealist-poet. For Aoki’s article in Japanese on the exhibit, see her blogspot, http://artthrob.exblog.jp/19026584/. Black and white plastic poems reproduced here are from the 1960s until Kitasono's death in 1978 and were included in issues of VOU magazine, published here with permission of Sumiko Hashimoto © 2014.

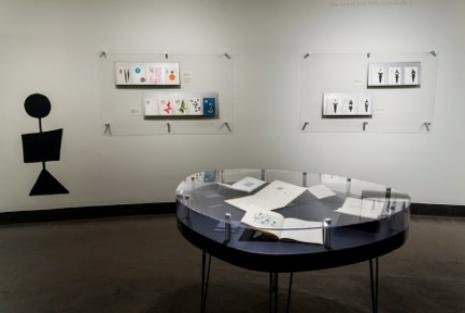

One of two rooms of the exhibit; photo by Lenny Lesser

Lenny Lesser

Lenny Lesser

Lenny Lesser

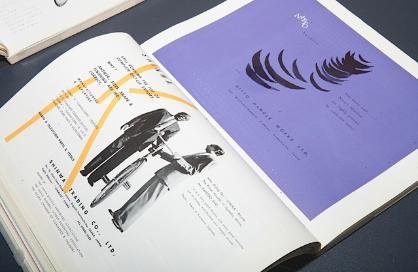

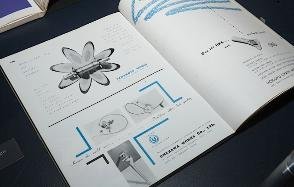

Bicycle Guide; photo by Peter Brenner ⓒ LACMA

Bicycle Guide; Peter Brenner

Lenny Lesser

Aoki Eiko: How would you characterize Kitasono’s esthetic in a few words?

Hollis Goodall: It changes very much; it mixes geometric and organic, sometimes tending more to the geometric than the organic, sometimes more to the organic. There is always a lot of white space. He tends to use grayed-down tones very selectively and then pure primary colors with equal ease. The main thing that one could say about him in a few words is that he takes a few selected elements and has an incredibly precise sense of balance using space with as much weight as the elements themselves. It’s an esthetic with nothing extraneous.

Aoki Eiko: Have you gotten any feedback from the visitors of the exhibition?

Hollis Goodall: A wide range of members of our staff have come over to look at it, which is interesting because, like me, so many people on our staff tend to miss exhibitions here thinking they will make them eventually but don’t. But people have made a point of getting over to see it and they like the fact that it blends different media so seamlessly between film and photography and the graphic arts and the language. That’s the kind of feedback that I’ve gotten, and also that the people who are interested in graphics truly love his graphic work.

Aoki Eiko: The title of the exhibition is “Kitasono Katue: Surrealist Poet.” Do you think he is correctly categorized as a Surrealist?

Hollis Goodall: That’s a really good question. I think he started out as a Surrealist, and he kept surrealist leanings. Later in his life, I think you would probably categorize him, if you’d categorize him, as a member of the avant-garde. His language tended to be more surrealistic and his graphics tended to be more avant-garde, particularly the post-war material that is heavily favored in this exhibition. We have these few from the pre-war era, and I think they would all fall into the category of surrealist. So I think his roots are in Surrealism.

Aoki Eiko: What was your process in going through Kitasono’s visual and textual output to distill it to what you have displayed?

Hollis Goodall: Well, oddly enough, I went through it just to see what was visually exciting to me. After that, I organized it into areas, and then I massaged it to fit the areas and physical spaces. But the first layer was what popped out at me.

Aoki Eiko: How long did this process take?

Hollis Goodall: A couple of months.

Aoki Eiko: Have you been working on this material for one or two years?

Hollis Goodall: With the writing and the editing, it would have been a couple of years.

Aoki Eiko: Has anything of your point of view changed over the two years of your involvement with the materials in the project? Have you had any epiphanies or discovered any insights into his work, or do you consider him as a kind of “open book” from the start rather than as a mystery who unravels with time?

Hollis Goodall: Well, I think he started out as a mystery that unraveled, and I do think there have been some eye-opening things, some of the discoveries came while talking with other people about his work—particularly with the graphic designers. You know, the fact that the colors are not seen in the West. There has been a lot of influence from Japanese graphics in the United States, I think since the 1970s. People found these things so exciting and why, and what it is about modern American graphics that they need to break the mold to look at Kitasono’s material. That was one thing I found exciting. The whole thing that I talked about earlier—the connection between his visual material and his words, his word poems—I think is something that has hit me even since the show has been on the walls, and seems to be coming more clear with looking and relooking at his material.

Aoki Eiko: It seems that even though he worked in many different media and inter-media, there is a certain consistent thread in his esthetic that does not seem to conflict and contrast. No matter what genre or media he goes into, he seems to be something similar.

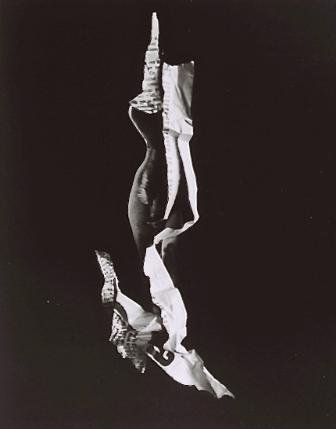

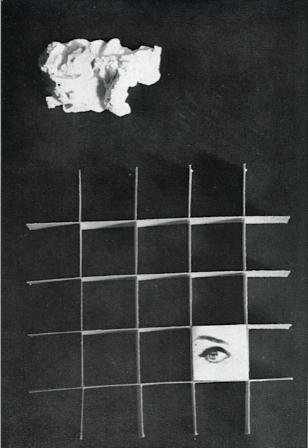

Hollis Goodall: Yes, a lot of artists will leap from one problem to another problem, and you’ll see an element that they particularly like that is a part of their vocabulary, that will come out again and again in different forms. But there is a consistency in Kitasono that has to do with space. And in the pictures that are very crowded, like “Forgotten Man” (see below) where he has strips of paper in the human form against a crumpled up paper background, by contrast to everything else, they feel very claustrophobic, so it seems that is what he is trying to express. Also, in his early Plastic Poems it seems that he uses a grid frequently, and in one place there will be an eye, and in other places there will be crumpled up bits of paper, other forms like a piece of wire and something like that. Possibly in those early works he was looking for some kind of organizing principle.

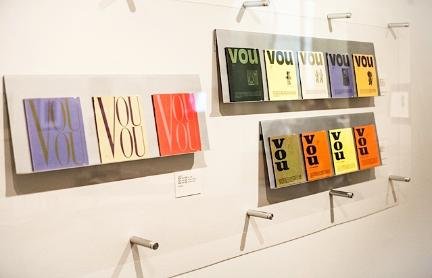

Aoki Eiko: His work on the covers of VOU magazine needed grids in order to put in the information of what issue number, what month. He found the grid—or pigeon holes—as a good system to fill in that information. And then he would use it without that info as a pure Plastic Poem design. And that might be related to some of the table photography that started with the Bicycle Guide. Interestingly, his commercial work with the bicycle parts came first, and his composing and photographing of them became a model of table photography that evolved into his Plastic Poetry. Well, maybe this leads into another question or there is no question… Kitasono Katue had two international peaks in his lifetime, from 1938 when he was introduced as a significant poet by Ezra Pound, and from 1958 when his Concrete poem “Monotonous Space” (1958) helped solidify the East-Asian penetration of the global movement. The first was purely textual and required English translation or writing of his poems to be understood. The second also was textually based, but purposely simple with a will to visualization. Now a third wave is occurring in Japan and Los Angeles with the museum showings of Kitasono’s work. The difference is this time the visuality— graphic and photographic—is outpacing the textual poetry aspect and coming to the fore.

Hollis Goodall: I think that is a function of where it is being shown. I think if it were shown in a library environment, there would be much more concentration on the language.

Aoki Eiko: That’s true, but that he’s reached the museum level is also interesting because most poets don’t. Maybe you’ve answered the question before I got to it!

Hollis Goodall: (laughing) Sorry!

Aoki Eiko: Being a crucial part of this third wave, how do you see the text to visual aspects of his work and how they flow together or don’t. I noticed, for example, that you put stanzas of his poems on the walls; one is appropriately about “shadows on a wall,” which I thought was a brilliant choice. Are you trying to show something about the visuality of the words (despite them being in English translation)…

Hollis Goodall: No, but that is a good idea.

Aoki Eiko: …as art equal to graphic and photographic design, or is it more to show that Kitasono was primarily a poet playing with language, or both?

Hollis Goodall: I think it was more about him not just playing with language but playing with image. When you juxtapose these different words and images against each other your mind necessarily struggles to create some kind of a new image. I think that happens also when you’re looking at his Plastic Poetry. If you look at something that is cut into the shape of a human, your mind—just as if it had been directed by words—says, “it must be human.” Somehow Kitasono has such a talent for cutting out a piece of paper and giving it energy, because not all trash is created equal. I think there are some people—mathematicians and musicians amongst them—who have a particular talent for spatial intelligence, and I think he must have been one of those people. He “pre-saw”; he didn’t just get there by playing, he pre- saw some of the material.

Aoki Eiko: How many people were involved in an exhibit like this, and what are some of their specialties?

Hollis Goodall: Well, people float in and float out. There were two to three conservators; five to seven prep guys at any one time; the construction guys—the cases were actually made by an outside vendor, but our construction people had to add weights to make them earthquake safe; the design department, one main person was in charge of design, and she had back-up from her boss; the two people from our exhibitions department kept floating through; security was in there, and then graphics. Education did the arrangements for the talks. The publications department did heavy editing. And there was a signage person, who also did the vinyl graphics. David in graphics also did the banners (an outside vendor made them). And of course the web people and audio-visual people including the videographer were also a crucial part of the large crowd. Afterwards, our photographer documented the exhibition, and web masters built

our web page and web editors reviewed the text of our blogs.

Aoki Eiko: It’s a huge teamwork effort with you as the leader. While setting up the exhibit, I heard that you had a table with a drawing of the exhibit spaces on it, noting where everything should go for everyone to work off. What happens to that “blueprint” of the exhibit, does it go into the museum’s archives?

Hollis Goodall: Well, I do keep a copy in my files. But I don’t keep copies of every generation, and it probably went through four generations before we got to the final one. We laid the whole show out in the conservation department lab, putting the actual artworks on dummy cutouts of all the tabletops. That way we could make sure about where everything was going to fit, and still there were some errors in the design, so we had to be nimble in the gallery. I always get a lot out of working with the prep people, because they’re mostly artists. They do get stimulated and they’ll talk about how they are excited by the work, and often they’ll give me new ways of seeing it from an artist’s point of view.

Kitasono Katue: plastic poems

“Forgotten Man,” photo by Kitasono Katue, later published in Stereo Headphones no. 7, special edition, 1975.