Uri Hertz

Art installations by Ai WeiWei in three Los Angeles galleries in 2018/19

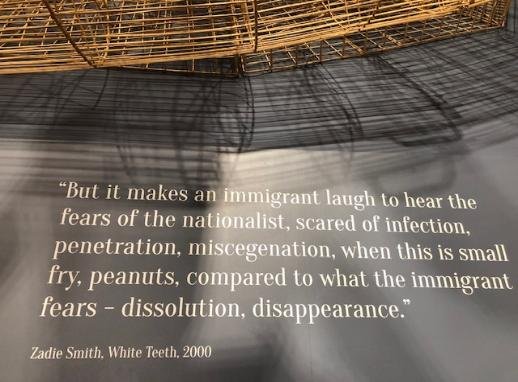

Life Cycles is an art installation by Ai WeiWei which explores the global refugee crisis, at Marciano Art Foundation, in a gigantic room at the old Masonic Temple on Wilshire. I went to see it with artist Linda Haim and East Asia scholar John Solt. Before reaching the main installation, we walked through an expansive room with a field of what appeared to be sunflower seeds made out of porcelain next to a field of teacup spouts. Hanging from extremely high ceilings in the main room were very large-scale bamboo sculptures with light casting their shadows on the ceiling and on the walls. Taking up the floor of the room was a gigantic boat, also fashioned out of bamboo. Numerous bamboo figures representing global refugees on the high seas were seated inside with creatures from the Chinese zodiac interspersed among them. Suspended on the wall were Chinese mythic figures crafted out of bamboo and silk by Chinese kite-makers based on Ai WeiWei’s designs. On the low base that the huge boat was mounted upon were epigrammatic citations from thinkers ranging from St. Augustine to Franz Kafka, each one bringing into focus a facet of the ethical core of the refuge question in this era. One of the most striking quotes was from Zadie Smith:

Filled with a feeling of consciousness expanded from being within the spatial dimensions of this expansive room and absorbing Ai WeiWei’s larger-than-life mixed-media art, as well as the temporal dimensionality of archetypal mythic figures transposed onto situations and conditions

of present-day world crises, we drove over to the Deitch Gallery in Hollywood. There we viewed Zodiac, an installation in a large warehouse among the sound stages above Willoughby. As we crossed La Brea, I mentioned to Linda and John that this was where I’d had a schoolboy paper-route delivering the Hollywood Citizen News well over half a century earlier. The gallery was nowhere near as cavernous as the old Masonic Temple, but it was extremely large. The center of the floor consisted of an art installation titled Stools (2013), a solid mass of nearly six thousand wooden stools from the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries. We agreed that manufactured stools would not possess the same aura of lived experience only derived from the touch of a workman’s hand. The most provocative and impressive piece was on the far wall in the form of wallpaper depicting in old-fashioned decorative style images which turned out to be surveillance cameras, handcuffs and other dystopian objects documenting the artist’s incarceration and house arrest in China

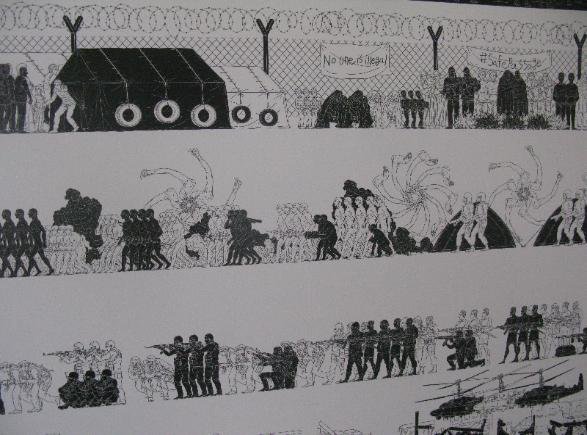

One week later, Linda and I went to UTA Artist Space in Beverly Hills to see the third Ai WeiWei installation: CAO/HUMANITY. As we entered the gallery from the street, there were six sculptures in a room to the side, each under glass. Among the most striking were three porcelain plates which appeared to be from a distant dynastic era. It became clear upon closer inspection that, juxtaposed with historical Chinese images, were war-torn village scenes with helicopters. Refugees were on the move, their belongings on their backs. The elaborately filigreed wallpaper in this room appeared at first to be ancient wall drawings on traditional themes, but, interspersed among them were lines of refugees along with refugee camps, tent cities, banners that said NO ONE IS ILLEGAL and #SAFE PASSAGE, ravaged cityscapes along with helicopters, soldiers with guns pointing in the same direction and other soldiers throwing tear gas grenades.

CAO, the title piece, in the center of the main room, is a field of marble blades of grass. The point made in the gallery brochure was that grass is trod upon like the refugees and other stateless wanderers, rejected by authoritarian nations where they seek asylum that are the primary theme of the installation. A week later, John Solt related to me that he had been at the gallery some days earlier and overheard a gallery staff person relating this interpretation to two women who were prospective buyers. He recounted to me that he walked over and interjected that another interpretation based on the bodhisattva’s vow not to attain enlightenment until every sentient being down to the lowliest blade of grass had been enlightened, could be an operative principle. As I gazed at the field of marble clumps of grass, I immediately grasped the Whitmanic intent of the artist, whether deliberate or not. Just as Walt Whitman, in Leaves of Grass, propagated the transcendentalist concept of each blade of grass being individual yet connected to others by an elaborate root system beneath the surface, not visible to the eye, Ai WeiWei’s blades of grass, sculpted out of marble, appeared to me to carry a parallel meaning. Yet to comprehend Ai WeiWei’s morphing of this vision, it is necessary to ask what Whitman’s 19th century concept of the person, individual yet connected to others and to the world, is worth in this 21st surveillance century with refugees turned away at borders and fascism on the rise with its predatory aggression?

Even beyond Ai WeiWei’s reification of Whitman’s leaves of grass is the temporal scope of his concept. The ancient Chinese techniques and styles applied in his works, along with what at first appears to be historic, traditional imagery, is juxtaposed with the present situation of stateless persons seeking refuge in authoritarian surveillance states that turn them away. It is a Brechtian epic concept that makes it possible to view the world of the past from the present moment and simultaneously view human situations in the present as if from a vantage point in the future